Efficiency with Costly Information:A Reinterpretation of Evidence from Managed Portfolios TOR Edwin J.Elton;Martin J.Gruber;Sanjiv Das;Matthew Hlavka The Review of Financial Studies,Volume 6,Issue 1 (1993),1-22. Stable URL: hup://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0893-9454%281993%296%3A1%3C1%3AEWCIAR3E2.0.CO%3B2-8 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use,available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html.JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides,in part,that unless you have obtained prior permission,you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles,and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal,non-commercial use. Each copy of any part of a STOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The Review of Financial Studies is published by Oxford University Press.Please contact the publisher for further permissions regarding the use of this work.Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/oup.html. The Review of Financial Studies 1993 Oxford University Press JSTOR and the JSTOR logo are trademarks of JSTOR,and are Registered in the U.S.Patent and Trademark Office. For more information on JSTOR contact jstor-info@umich.edu. ©2003 JSTOR http://www.jstor.org/ Tue Feb1801:31:122003

Efficiency with Costly Information:A Reinterpretation of Evidence from Managed Portfolios Edwin J.Elton Martin J.Gruber Sanjiv Das Matthew Hlavka New York University We investigate the informational efficiency of mutual fund performance for the period 1965-84. Results are sbown to be sensitive to the measure- ment of performance cbosen.We find that returns on S&P stocks,returns on non-S&P stocks,and returns on bonds are significant factors in per- formance assessment.Once we correct for the impact of non-S&P assets on mutual fund returns, we find that mutual funds do not earn returns tbat justify tbeir information acquisition costs.This is consistent witb results for prior periods. The evaluation of professional money management has long been a topic of considerable interest to finan- cial economists.Two developments have stimulated renewed interest in this topic.The first is the work of Grossman (1976)and Grossman and Stiglitz (1980). They argue that trades by informed investors take place at prices that compensate these investors for the cost of becoming informed.Under these conditions,it is The authors would like to thank Eugene Fama,Andrew Lo,William Sharpe, and the referee (Bruce Lehmann)for helpful comments and suggestions on an earlier version of this article.We have benefited from useful suggestions received at workshop presentations at MIT,the University of Chicago,and the University of Michigan and presentation at the European Finance Asso- ciation.Address correspondence to Edwin J.Elton and Martin Gruber,Stern School of Business,Department of Finance,44 West 4th Street,New York, NY10012. Tbe Review of Financial Studtes 1993 Volume 6,number 1,pp.1-22 1993 The Review of Financial Studies 0893-9454/93/$1.50

The Review of Financial Studies/v6n 1 1993 possible for informed investment managers to pass on the cost of analysis to their clients and for their clients to be no worse off after reimbursing managers for the cost of becoming informed.Managers who charge higher fees do not necessarily earn lower returns for their clients.Higher fees may or may not be associated with lower returns, depending not on the efficiency of security markets,but rather on the efficiency of the market for money managers. The second development stems from the work of Roll (1977)and Ross (1977)and its implication for the evaluation of the money man- ager.Roll's argument against the use of CAPM as a benchmark for performance together with Ross's discovery of arbitrage pricing theory has led to questions about the appropriate benchmarks against which to judge abnormal performance. Recent work,particularly that of Lehman and Modest (1987),Admati et al.(1986),Conner and Korajczyk (1991),and Grinblatt and Titman (1989),raise further questions about the appropriate benchmark to use in evaluating performance.In particular,Lehman and Modest (1987)stress the sensitivity of performance to the benchmark chosen and the need to find a set of benchmarks that represent the common factors determining security returns.This literature should be con- trasted with a set of literature that seems to indicate that a single- index model provides an adequate description of portfolio returns and that the evaluation of the returns is reasonably insensitive to the definition of the index used.For example,Roll (1971)found that three market proxies provided nearly identical performance measures for randomly selected portfolios.Copeland and Mayers (1982)found that inferences about the value Line Enigma were unaffected by the choice of a performance benchmark. Our purpose in this article is to show that even a very parsimonious description of the proxies generating returns on portfolios of bonds and stocks can lead to very different and superior inferences about the attributes of active portfolio management compared to a single index.We use as an example the data used (and conclusions reached) in a recent study of mutual fund performance by Ippolito (1989).The Ippolito study is important because it is the first test of the expanded (Grossman)definition of market efficiency using data on managed portfolios.In addition,Ippolito's study is interesting because his results and conclusions are different from those reached in a long series of mutual fund studies. Ippolito has at least two findings that are important and consistent with a theory of efficiency with informed investors. (1)Estimated risk adjusted return (@)for the mutual fund industry 2

Efficiency with Costly Information is greater than zero even after accounting for transaction costs and expenses.Ippolito attributes nonnegative a to the existence of informed actions by management. (2)There does not seem to be any evidence that turnover,man- agement fees,or expenses are associated with inferior returns,net of management fees and expenses. These results and conclusions are very different from those reached by earlier researchers [see Jensen (1968),Friend,Blume,and Crockett (1970),and Sharpe (1966)].In particular,they are different from the results presented by Jensen,who found a negative a on average for a broad sample of mutual funds over the periods 1955-1964 and 1945- 1964. In this article,we show that Ippolito's results are primarily due to the difference in the performance of non-S&P 500 assets in the Ippoli- to period (1965-1984)compared to the performance of these assets in the Jensen period.1 Furthermore,once we explicitly account for mutual funds holding non-S&P assets,the results of the type of anal- ysis Ippolito performs change and are identical to those found in earlier studies. In the first section of this article,we examine the effect of holding non-S&P equities and bonds on alphas of mutual funds.Mutual funds have historically held some stocks not in the s&P index and held some stocks in the S&P index in proportions below their weighting in the S&P index.We shall see that holding non-S&P stocks would cause negative a's for funds over the earlier period studied by Jensen and positive a's for funds over the period studied by Ippolito,even if management had no selection ability.In both the earlier period and the latter period,the effect of bonds being part of the portfolio had very little impact on a.2 Having documented in the first section of this article two influences that could account for the positive a's found by Ippolito,we then correct for these influences.This is done by introducing two new indexes into the standard one-index performance measurement model. This allows us to examine if funds have a positive a above and beyond that arising from extending holdings beyond the s&P 500. In the final section,we examine the influence of expenses and turnover on a when we have explicitly taken into account the effect of non-S&P assets. In part,his results are also due to data errors that led to a particular bias.This will be explored in later sections of the article. Bonds impact a indirectly if the presence of bonds means that the aggregate portfolio has a smaller percentage of non-S&P stocks. 3

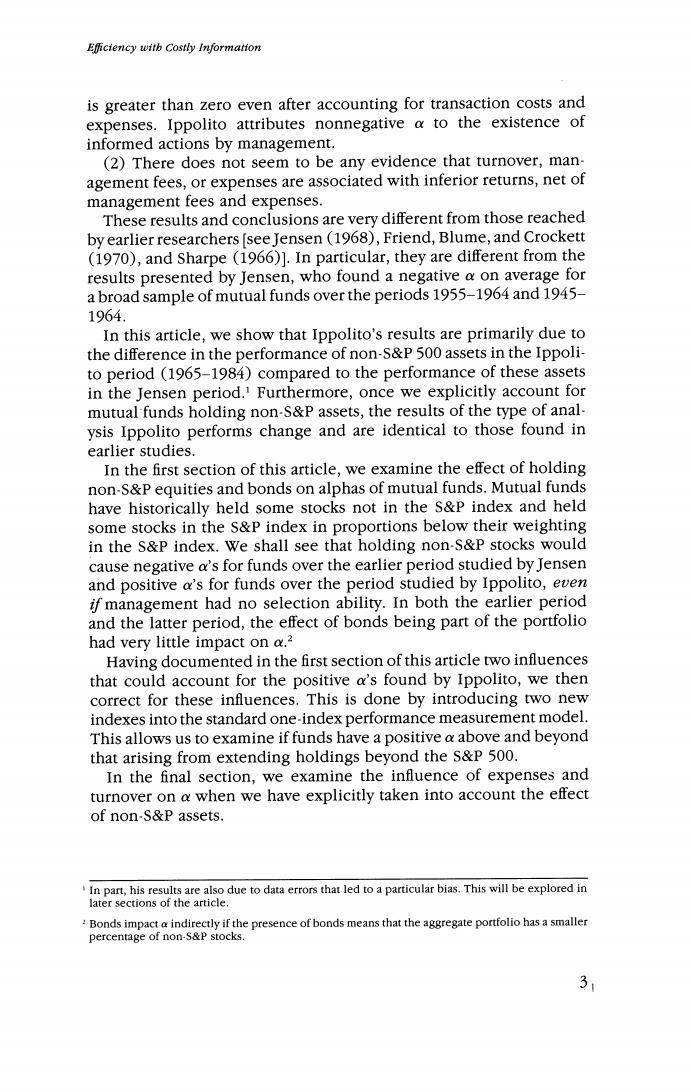

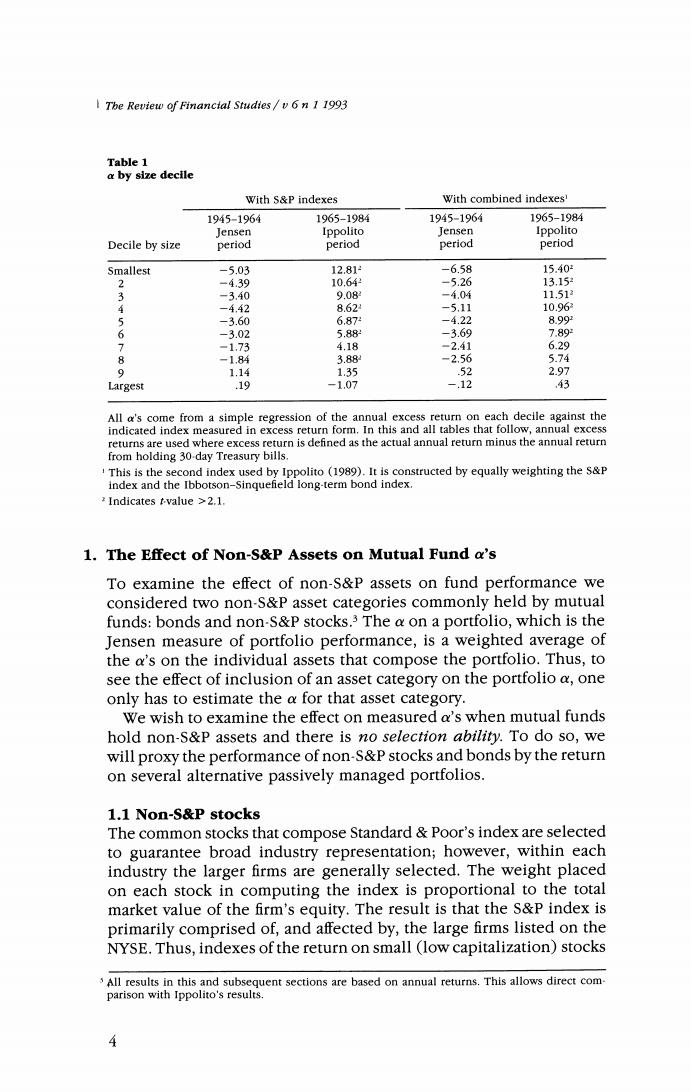

Tbe Review of Financtal Studies/v 6 n 1 1993 Table 1 a by size decile With S&P indexes With combined indexes 1945-1964 1965-1984 1945-1964 1965-1984 Jensen Ippolito Jensen Ippolito Decile by size period period period period Smallest -5.03 12.812 -6.58 15.40- 2 -4.39 10.64 -5.26 13.15 3 -3.40 9.08 -4.04 11.51 4 -4.42 8.62 -5.11 10.963 5 -3.60 6.87 -4.22 8.992 6 -3.02 5.88 -3.69 7.89 7 -1.73 4.18 -2.41 6.29 8 -1.84 3.88 -2.56 5.74 9 1.14 1.35 .52 2.97 Largest .19 -1.07 -.12 ,43 All a's come from a simple regression of the annual excess return on each decile against the indicated index measured in excess return form.In this and all tables that follow,annual excess returns are used where excess return is defined as the actual annual return minus the annual return from holding 30-day Treasury bills. This is the second index used by Ippolito(1989).It is constructed by equally weighting the s&P index and the Ibbotson-Sinquefield long-term bond index. Indicates tvalue >2.1. 1.The Effect of Non-S&P Assets on Mutual Fund a's To examine the effect of non-S&P assets on fund performance we considered two non-S&P asset categories commonly held by mutual funds:bonds and non-S&P stocks.3 The a on a portfolio,which is the Jensen measure of portfolio performance,is a weighted average of the a's on the individual assets that compose the portfolio.Thus,to see the effect of inclusion of an asset category on the portfolio a,one only has to estimate the a for that asset category. We wish to examine the effect on measured a's when mutual funds hold non-S&P assets and there is no selection ability.To do so,we will proxy the performance of non-S&P stocks and bonds by the return on several alternative passively managed portfolios. 1.1 Non-S&P stocks The common stocks that compose Standard Poor's index are selected to guarantee broad industry representation;however,within each industry the larger firms are generally selected.The weight placed on each stock in computing the index is proportional to the total market value of the firm's equity.The result is that the S&P index is primarily comprised of,and affected by,the large firms listed on the NYSE.Thus,indexes of the return on small (low capitalization)stocks All results in this and subsequent sections are based on annual returns.This allows direct com parison with Ippolito's results