The incidence of invertebrate pests varies with regional conditions,and a number of trials have shown no yield ected ryegrass in region. 2.7 PRG Endophyte Animal Health Effects(Mainly in Sheep) Sheep grazing different seedlines of PRG in an experiment at Lincoln were very differently affected by ryegrass staggers.The pasture causing the worst staggers had high levels of infection with endophyte,while the sheep free of staggers were grazing a pasture with almost no endophyte (Fletcher Harvey,1981;Fletcher,1982).This led to an intensive programme documenting and quantifying the effects of endophyte on sheep (Table 2) The precise effects of the staggers toxin on nerve and muscle function(McLeay Smith 1999;Munday-Finch Garthwaite,1999)have been described,and genetic resistance in sheep has been measured (Mornis et al..1999). has been responsible for the l ss of 900 shee p at a cost of on property (Milr 1999 Deaths Prerc n etal,1992. 100 .1993:Fet (Eerens et al..1992). Table 2:Major discoveries of effects of endophyte-infected ryegrass herbage on health and performance of grazing livestock.(From Easton et al.,2001). Discovery Reference Lolium endophyte causes ryegrass staggers. Fletcher Harvey (1981) Lolium endophyte reduces rate of liveweight gain in Fletcher(1983) lambs grazing PRG. Lolium endophyte in PRG depressed serum Fletcher Barrell (1984) prolactin in lambs;a link established between ryegrass and fescue toxicosis. The first lolitrem-free endophyte in PRG evaluated, Fletcher et al.(1991) showing possible elimination of ryegrass staggers Lolium endophyte linked to faecal contamination Fletcher et a/(1993):Pownall et al. (dags). (1993 Livestock grazing herbage infected with AR Fletcher Easton(1997) endophyte strain, free of ergovaline and lolitrem B. are tree of all toxic ettects eep can be bred for resistance to RGS. Morris et al.(1999) Milk production of dairy cows sometimes affected by Blackwell Keogh (1999);Clark et dophyte. a/.(1996);Thom et al.(1999 Metabolites other than lolitrem unpublished ryegrass/endophyte associations can cause ggers symptoms in grazing livestoc 8,288 2001)cited by Easton PAGE11

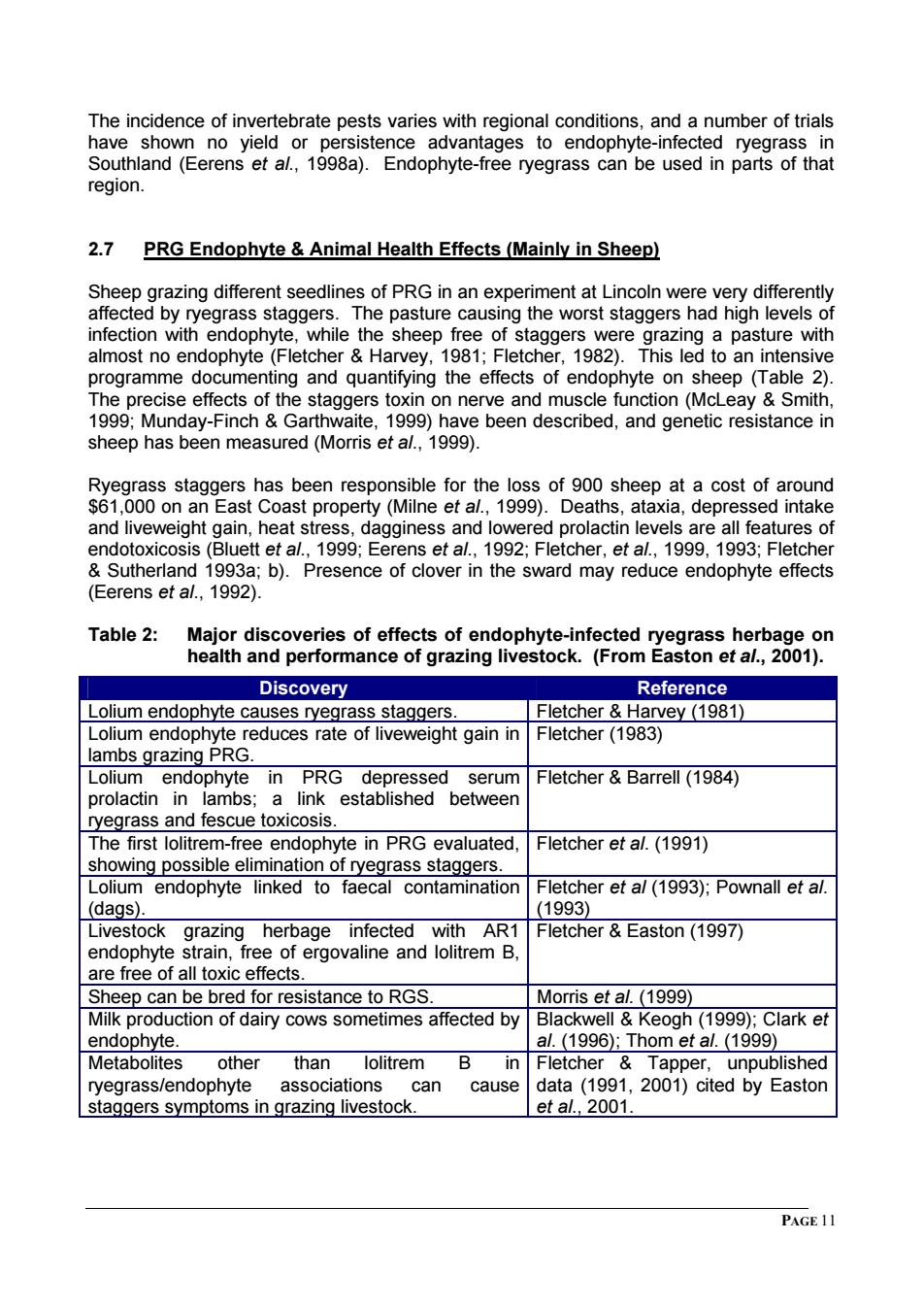

The incidence of invertebrate pests varies with regional conditions, and a number of trials have shown no yield or persistence advantages to endophyte-infected ryegrass in Southland (Eerens et al., 1998a). Endophyte-free ryegrass can be used in parts of that region. 2.7 PRG Endophyte & Animal Health Effects (Mainly in Sheep) Sheep grazing different seedlines of PRG in an experiment at Lincoln were very differently affected by ryegrass staggers. The pasture causing the worst staggers had high levels of infection with endophyte, while the sheep free of staggers were grazing a pasture with almost no endophyte (Fletcher & Harvey, 1981; Fletcher, 1982). This led to an intensive programme documenting and quantifying the effects of endophyte on sheep (Table 2). The precise effects of the staggers toxin on nerve and muscle function (McLeay & Smith, 1999; Munday-Finch & Garthwaite, 1999) have been described, and genetic resistance in sheep has been measured (Morris et al., 1999). Ryegrass staggers has been responsible for the loss of 900 sheep at a cost of around $61,000 on an East Coast property (Milne et al., 1999). Deaths, ataxia, depressed intake and liveweight gain, heat stress, dagginess and lowered prolactin levels are all features of endotoxicosis (Bluett et al., 1999; Eerens et al., 1992; Fletcher, et al., 1999, 1993; Fletcher & Sutherland 1993a; b). Presence of clover in the sward may reduce endophyte effects (Eerens et al., 1992). Table 2: Major discoveries of effects of endophyte-infected ryegrass herbage on health and performance of grazing livestock. (From Easton et al., 2001). Discovery Reference Lolium endophyte causes ryegrass staggers. Fletcher & Harvey (1981) Lolium endophyte reduces rate of liveweight gain in lambs grazing PRG. Fletcher (1983) Lolium endophyte in PRG depressed serum prolactin in lambs; a link established between ryegrass and fescue toxicosis. Fletcher & Barrell (1984) The first lolitrem-free endophyte in PRG evaluated, showing possible elimination of ryegrass staggers. Fletcher et al. (1991) Lolium endophyte linked to faecal contamination (dags). Fletcher et al (1993); Pownall et al. (1993) Livestock grazing herbage infected with AR1 endophyte strain, free of ergovaline and lolitrem B, are free of all toxic effects. Fletcher & Easton (1997) Sheep can be bred for resistance to RGS. Morris et al. (1999) Milk production of dairy cows sometimes affected by endophyte. Blackwell & Keogh (1999); Clark et al. (1996); Thom et al. (1999) Metabolites other than lolitrem B in ryegrass/endophyte associations can cause staggers symptoms in grazing livestock. Fletcher & Tapper, unpublished data (1991, 2001) cited by Easton et al., 2001. PAGE 11

Ryegrass staggers is the most obvious and immediately serious effect,but many other indicators of sheep health and productivity are affected.Notable among these are the effects on liveweight gain,on serum prolactin levels and on body temperature control Liveweight gain of lambs,pre-and post-weaning,and of older sheep has been shown to be depress (Bluett et al. Fletche son er al. Depres thar 30%,sustair er et al. 099 0° n the e many wee been recorde and eight' and r esulted in reduced of and twir lambs Serum prolactin concentration in sheep responds to ambient temperature,with levels rising from typically below 50 ng/ml at moderate temperatures,to above 200 ng/ml in warm conditions.Sheep grazing endophyte-infected PRG do not respond in this way,so that at higher temperatures,there is a wide difference between animals grazing infected and endophyte-free herbage(Fletcher et al.,1997).These results conform to published American reports of cattle grazing tall fescue. Depression of serum prolactin is now recognised as a sensitive indicator of exposure of livestock to endophyte-related toxicity. tgrazienendopnYteante wne PRG frequently show a higher d femp endopnye-inie fl Ce high am sheep grazing t PRG may exhibit severe panting( 1999 grass pastures,but other endophyte-related me of the same compounds involved. Kramer et al.(1999)studied the effects of endophyte infected tall fescue of the fertility of Finn x Romney 2-tooth ewes.Groups (n=20)were grazed on either of two lines of endophyte-infected tall fescue,one producing ergovaline(EV+)and the other ergovaline free (EV-)for two weeks and then mated on the treatments. Ovulation rate.conception rate,and numbers of lambs carried were recorded. Levels of serum prolactin and ermine Ergovaline levels in the herbage were mg/g ar ng/g n an pas respe EW sgra☑ ng tne EV+ lower ulat n rates or lam P<0.001 redu in the FV nat the that similar effe cte razin ndophyte-infected nial pastures contai rgovaline and that further trials are being underta n to exar ye this Keogh(2002)reports an increased incidence of pneumonia in lambs grazing ryegrass pastures on farms in Northland,which may be linked to the heat stress caused by ergovaline (Keogh pers.comm.). PAGE 12

Ryegrass staggers is the most obvious and immediately serious effect, but many other indicators of sheep health and productivity are affected. Notable among these are the effects on liveweight gain, on serum prolactin levels and on body temperature control. Liveweight gain of lambs, pre- and post-weaning, and of older sheep has been shown to be depressed by grazing endophyte-infected PRG (Bluett et al., 1999; Fletcher & Sutherland, 1993; Watson et al., 1999; Fletcher et al., 1999). Depression in gain of more than 30%, sustained over many weeks, has been recorded for hoggets, and of up to 90% for lambs. In the study of Watson et al. (1999), grazing endophyte pasture depressed ewe intake and liveweight, and resulted in reduced growth rates of suckling single and twin lambs. Serum prolactin concentration in sheep responds to ambient temperature, with levels rising from typically below 50 ng/ml at moderate temperatures, to above 200 ng/ml in warm conditions. Sheep grazing endophyte-infected PRG do not respond in this way, so that at higher temperatures, there is a wide difference between animals grazing infected and endophyte-free herbage (Fletcher et al., 1997). These results conform to published American reports of cattle grazing tall fescue. Depression of serum prolactin is now recognised as a sensitive indicator of exposure of livestock to endophyte-related toxicity. Animals grazing endophyte-infected PRG frequently show a higher body temperature, particularly when held in conditions of high ambient temperature and humidity, the difference sometimes being a full Celsius degree. Associated with this, sheep grazing endophyte-infected PRG may exhibit severe panting (Fletcher et al., 1999). Ryegrass staggers is a problem specific to ryegrass pastures, but other endophyte-related symptoms in livestock are similar to some effects of infected tall fescue, with some of the same compounds involved. Kramer et al. (1999) studied the effects of endophyte infected tall fescue of the fertility of Finn x Romney 2-tooth ewes. Groups (n=20) were grazed on either of two lines of endophyte-infected tall fescue, one producing ergovaline (EV+) and the other ergovaline free (EV-) for two weeks and then mated on the treatments. Ovulation rate, conception rate, and numbers of lambs carried were recorded. Levels of serum prolactin and ergovaline in the pasture were determined. Ergovaline levels in the herbage were 3.30+0.60 mg/g and 0mg/g in the EV+ and EV- pastures, respectively. Ewes grazing the EV+ treatment had significantly lower (P<0.05) ovulation rates and number of lambs carried to 90 days of pregnancy than the EV- group. Serum prolactin was significantly (P<0.001) reduced in the EV+ group. The authors concluded that the results indicated that similar effects may occur in ewes grazing endophyte-infected perennial ryegrass pastures containing ergovaline and that further trials are being undertaken to examine this possibility. Keogh (2002) reports an increased incidence of pneumonia in lambs grazing ryegrass pastures on farms in Northland, which may be linked to the heat stress caused by ergovaline (Keogh pers. comm.). PAGE 12