3941 PLENARY SPEECHES his status as a successful farmer in Yucatan.To local merchants DF is a preferred customer, one who makes frequent trips to supply his busy restaurant and who spends a lot of money On this occasion he is stopp ing in to check out supplies and place rders,eager to show the resear her his routines and to demonstrate the rudiments of Maya the merchants ar learning.(For transcription conventions,see Appendix.) 3.1 An ecology of multilingual space 3.1.1 At the Vietnamese grocery The first excerpt occurs in a grocery store with Vietnamese writing on its awning.The er,whom DF introduces as Juan,has been speaking to DF in English,who wers him in Spanish.Juan is busy loading meat from the freezer into th isplay case,and this exchange comes at the end of a short conversation about the meat that DF needs. Excerpt I how much panza you want? (tripe) 2 DF: oy a comprar cinco libras de panza I'm going to buy 5lbs of tripe 3 uan: OK manana DE: Ama'alob. good 5 OKI 6 DE vDios bo dik thanks J /bo dik ǒ DF: saama tomorrow 9 Juan: @@, 10 @@ 11 saama 12 DF: nd Maya inde the ongoing discourse.At the end of a transaction in which Juan has been speaking a mix of English and Spanish,and DF has been speaking exclusively Spanish.luan and DF tak leave-Juan in English,DF in Maya.Taking leave is always a delicate part of any verbal exchange as it has to sum up the exchange,make plans for future exchanges,and perform a ou choice ca abva bome forroudd d acceptable leave- But in multili ingual exch es like th ince Juan ha addressed DF in English and had been responded to in Spanish,Juan's'OK'in line 3 can be seen to be oriented not only toward the content of DF's utterance,but toward the language that DF chose to speak in.A gloss of this 'OK'might be 'I agree to sell you 5lbs of tripe re toepond o you Spansh o themac 2018at vailable a

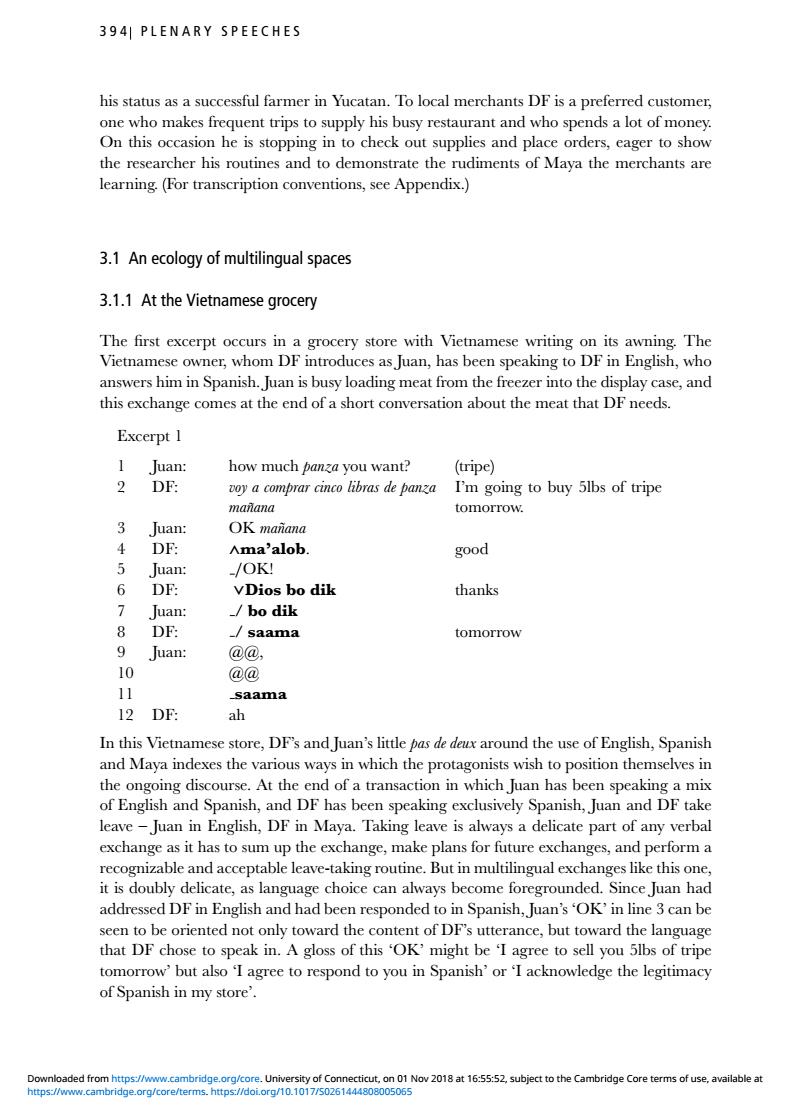

394 PLENARY SPEECHES his status as a successful farmer in Yucatan. To local merchants DF is a preferred customer, one who makes frequent trips to supply his busy restaurant and who spends a lot of money. On this occasion he is stopping in to check out supplies and place orders, eager to show the researcher his routines and to demonstrate the rudiments of Maya the merchants are learning. (For transcription conventions, see Appendix.) 3.1 An ecology of multilingual spaces 3.1.1 At the Vietnamese grocery The first excerpt occurs in a grocery store with Vietnamese writing on its awning. The Vietnamese owner, whom DF introduces as Juan, has been speaking to DF in English, who answers him in Spanish. Juan is busy loading meat from the freezer into the display case, and this exchange comes at the end of a short conversation about the meat that DF needs. Excerpt 1 1 Juan: how much panza you want? (tripe) 2 DF: voy a comprar cinco libras de panza manana ˜ I’m going to buy 5lbs of tripe tomorrow. 3 Juan: OK manana ˜ 4 DF: ∧ma’alob. good 5 Juan: /OK! 6 DF: ∨Dios bo dik thanks 7 Juan: / bo dik 8 DF: / saama tomorrow 9 Juan: @@, 10 @@ 11 saama 12 DF: ah In this Vietnamese store, DF’s and Juan’s little pas de deux around the use of English, Spanish and Maya indexes the various ways in which the protagonists wish to position themselves in the ongoing discourse. At the end of a transaction in which Juan has been speaking a mix of English and Spanish, and DF has been speaking exclusively Spanish, Juan and DF take leave – Juan in English, DF in Maya. Taking leave is always a delicate part of any verbal exchange as it has to sum up the exchange, make plans for future exchanges, and perform a recognizable and acceptable leave-taking routine. But in multilingual exchanges like this one, it is doubly delicate, as language choice can always become foregrounded. Since Juan had addressed DF in English and had been responded to in Spanish, Juan’s ‘OK’ in line 3 can be seen to be oriented not only toward the content of DF’s utterance, but toward the language that DF chose to speak in. A gloss of this ‘OK’ might be ‘I agree to sell you 5lbs of tripe tomorrow’ but also ‘I agree to respond to you in Spanish’ or ‘I acknowledge the legitimacy of Spanish in my store’. https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444808005065 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Connecticut, on 01 Nov 2018 at 16:55:52, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

CLAIRE KRAMSCH:ECOLOGICAL FL EDUCATION J395 Inine DFsuddenly swithes to Maya Because the store is located ina predominantly Spanish-speaking area of San Francisco,DFs efforts to get Juan and other merchants to respond to him in Maya has been a form of public resistance to a Spanish colonial discourse which holds Maya in low esteem among Mexicans.Here,a Vietnamese clerk serves as an unwitting catalyst for DF's efforts to provide a place for himself between the polarity social millston onging o a recent of migrants with dubious immigration status,in some neighborhoods of San Francisco Maya can be made to yield a different social capital.Vis-a-vis third ethnic groups,i.e.,immigrants that are neither Mexicans nor Anglos,DFs use of Maya gives him a prestige of distinction vis-a-vis Mexicans,Spanish gives him a distinction at par with Anglos Laughing in lines 9-10,Ju is both a used and slightly embarra ssed at havin roduce Maya sound n fro of th Anglo visito span neighborhood,English and Spanish would be the two unmarked codes,followed perhaps by Vietnamese as the storeowner's language,but Maya is definitely marked.However,it has,in this case,acquired some historical presence due to DF's repeated efforts to teach the local merchants some Maya,so we can interpret Juan's chuckle as a sign that he is both willing e and ambivaler worth noting that DF does not adr nister his little Maya lesson in al store,for example,he uses Spanish throughout even when admonishing the clerk that her ability to understand Maya is improving (see excerpt 6,lines 138-141). 3.1.2 At the Chinese grocery The next three excerpts come from a Chinese-run grocery store,where DF has stopped to find out how much masa(corn-flour dough)his son had picked up earlier in the dav. Excerpt 2 I DE ((TO BUTCHER IN MAYA)) 2 Butcher: sisisi DF: ((TO CLERK))buenas. tengo<>m maestra I'm with my teacher 5 AW: <LO HILO> teacher Clerk OH [@ 8 DF: 9 es mi maestra She's my teacher 10 ah 11 ch-nomds,este,pase a preguntar/ I just uh came to ask 12 the masa that my son took. 13 80 and now 22 Clerk si bien. yes good. 2 le toco masa acd ahora he'll take masa here now

CLAIRE KRAMSCH: ECOLOGICAL FL EDUCATION 395 In line 4, DF suddenly switches to Maya. Because the store is located in a predominantly Spanish-speaking area of San Francisco, DF’s efforts to get Juan and other merchants to respond to him in Maya has been a form of public resistance to a Spanish colonial discourse which holds Maya in low esteem among Mexicans. Here, a Vietnamese clerk serves as an unwitting catalyst for DF’s efforts to provide a place for himself between the polarity Spanish–English that divides much of California today. Whereas speaking Maya can be a social millstone in Yucatan and in California it marks speakers as belonging to a recent wave of migrants with dubious immigration status, in some neighborhoods of San Francisco Maya can be made to yield a different social capital. Vis-a-vis third ethnic groups, i.e., immigrants ` that are neither Mexicans nor Anglos, DF’s use of Maya gives him a prestige of distinction vis-a-vis Mexicans, Spanish gives him a distinction at par with Anglos. ` Laughing in lines 9–10, Juan is both amused and slightly embarrassed at having to produce Maya sounds in front of the Anglo visitor. In the usual hierarchy of codes in this Hispanic neighborhood, English and Spanish would be the two unmarked codes, followed perhaps by Vietnamese as the storeowner’s language, but Maya is definitely marked. However, it has, in this case, acquired some historical presence due to DF’s repeated efforts to teach the local merchants some Maya, so we can interpret Juan’s chuckle as a sign that he is both willing to respect DF’s language and ambivalent about his own legitimacy as a Maya speaker. It is worth noting that DF does not administer his little Maya lesson in all stores. In the Chinese store, for example, he uses Spanish throughout even when admonishing the clerk that her ability to understand Maya is improving (see excerpt 6, lines 138–141). 3.1.2 At the Chinese grocery The next three excerpts come from a Chinese-run grocery store, where DF has stopped to find out how much masa (corn-flour dough) his son had picked up earlier in the day. Excerpt 2 1 DF: ((TO BUTCHER IN MAYA)) 2 Butcher: si si si 3 DF: ((TO CLERK)) buenas . 4 vengo <?> mi maestra I’m with my teacher 5 AW: <LO HI LO> 6 teacher 7 Clerk: OH [@] 8 DF: [ah] 9 es mi maestra\ She’s my teacher 10 ah 11 eh-nomas, este, pas ´ ´e a preguntar/ I just uh came to ask 12 la masa que agarro mi hijo ´ \ the masa that my son took, 13 ochenta y ahora/ 80 and now . 22 Clerk si bien. yes good. 23 le toco masa aca ahora ´ he’ll take masa here now https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444808005065 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Connecticut, on 01 Nov 2018 at 16:55:52, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at